400 Years Later—Has “O Give Thanks” Made a Difference?

Four centuries ago this autumn—“. . . it was probably in late September or early October [1621], soon after [the Pilgrim’s] crop of corn, squash, beans, barley, and peas had been harvested” (Nathaniel Philbrick Mayflower 117)—the decimated band of immigrant refugees to these shores had by a breath barely survived that treacherous winter before.

The numbers speak volumes: “ . . . 45 of the original 102 colonists died during the first winter. There were 17 fatalities in February alone. Many succumbed to the elements, malnutrition, and diseases such as scurvy. Frequently two or three died on the same day. Four entire families perished and there was only one family that didn’t lose at least one member. Of the 18 married women, 13 died. Only three of 13 children perished, probably because mothers were giving their share of food to the children” (www.weatherconcierge.com/the-pilgrims-barely-survived-a-harsh-first-wint...).

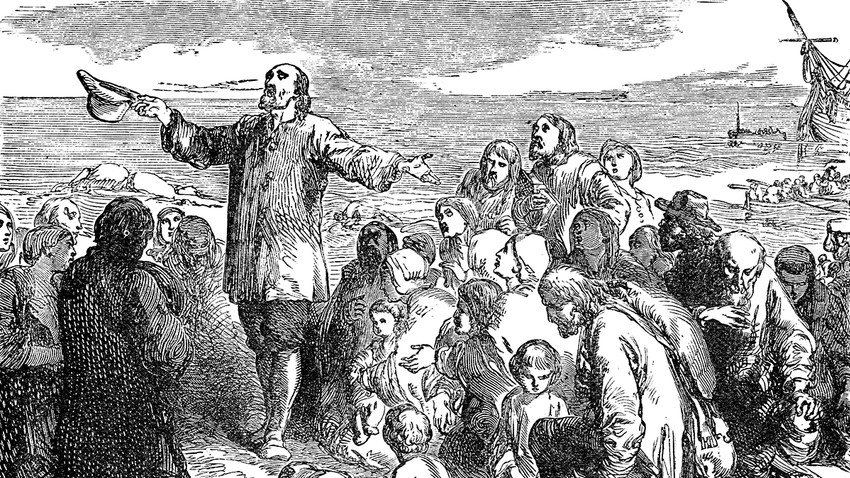

And yet crippled though they were by those losses, these fifty-two English trans-Atlantic survivors turned a subsequent bountiful summer crop into a three-day harvest feast for the fledgling band of Pilgrims and their benefactor guests, Chief Massasoit, and his ninety Wampanoag warriors. “O give thanks unto the Lord.”

(Although truth be told, there is no celebration in the Wampanoag Nation today. In fact, “for the Wampanoags and many other American Indians, the fourth Thursday in November is considered a day of mourning, not a day of celebration” (www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/11/04/thanksgiving-anniversary-wampa...). Once a thriving nation between 30,000 and 100,000 in eastern Massachusetts, Wampanoags today number 2,800—their homeland gone, their own numbers decimated. “O give thanks unto the Lord”?)

Four hundred years ago, of course, William Bradford had no inkling of the subsequent history. As the elected governor of these English immigrants, he declared their time of communal gratitude to be an occasion to “[gather] the fruit of our labors” and “rejoice together . . . after a more special manner” (Philbrick 117).

Years after that first “thanksgiving,” the aged Bradford looked back to testify: “What could now sustain them [those survivors] but the spirit of God and His grace? May not and ought not the children of these fathers rightly say: ‘Our fathers were Englishmen which came over this great ocean, and were ready to perish in the wilderness; but they cried unto the Lord, and He heard their voice and looked on their adversity [see Deuteronomy 26:7]’” (Philbrick 46).

And “may not and ought not” the children of America today—we who come from every land to inhabit this same land—join that ancient chorus: “O give thanks unto the Lord, for He is good, and His love endures forever” (Psalm 136).

But with that glad acclamation shall we not also resolve to be “Love on the Move” to the “strangers within our gates,” the refugees and immigrants who settle in our midst? Of all people, shall we not extend the compassion of our Lord Jesus to the alienated, the disenfranchised, the marginalized residents of this land? “O give thanks unto the Lord.”